Chapter 12

I had a moment of peculiar introspection. Maybe not even introspection. Recollection maybe.

Less than an hour ago, I’d considered killing all five of them for the blade. That would have been a bad fight, but I was desperate. Now, I had the sword, they stood to let me take it, but I’d have to pay them nigh everything I had.

Two hundred and fifty thousand sesteres was a lot of money. I told myself not to get wrapped up in comparative value. They had a nice house, probably worth a million or more, and it made the quarter ton I’d offered them look light.

Forget all that. The assassins would have been paid a million, half up front and gone, half on completion. Half-a-million sesteres lay in cases I’d hid around the city, a lot of money, and if this deal walked, I’d walk away with a quarter ton. If I was smart with it, smarter than the idiots I knew or the fool I had been, I could stretch a that a long way. I knew people who knew money. Northshore had a finance department, and I had friends. I could do well.

But I didn’t pay them, with all four drops I’d have more, and I could do much better. That’s the way money works. More is a lot better than what you have.

All the risk was front-loaded. Draw now, kill everyone, leave. It nicely silenced any talking mouths too.

That was what Koru had meant to do to me.

It wasn’t any complicated ethics I thought of. I thought of people: Koru, Astras, Hoarfast, and Seraphine. Seraphine had let them try to kill me. They had done unto me what I considered doing onto these others. There are rules and laws about killing. We had religions like cow turds on a ranch, and some variation of ‘Don’t kill people’ seemed present in all of them. I didn’t care about any of that.

I thought of Koru.

I warned Apseto. “I’m going to point this toward that wall.”

He moved clear but stayed between me and the windows.

I rotated the blade, keeping the tip away from him and avoiding anything that could be interpreted as a slashing motion.

The edge was flecked with stars. They moved inside the steel, floating like dust specks in water. A lighter type of steel, almost milky, made up the cutting surface. The metal body was darker but polished like a mirror. I saw distorted images of myself and the Hemlin cousins. The straight edge was as thick as my pinky finger, and just forward of it ran a groove on both sides. Up and down it dripped shadows, a slow dissipation of darkness into air.

The bottom had a fake stamp, artfully forged. A flower crossed a scepter, and below it stood three runes. No one read runes any more. I didn’t either, but I’d memorized these three: All Things Ending.

Badly-engraved writing on the hilt said, ‘Saber by Hasso, Twenty Fourth of Messidor.’

Hasso had left a maker’s mark on a forgery. I contemplated that for a moment.

“Sleep forever,” I whispered, and the sword glittered. My words ran down the blade like a wave breaking through a tide of phosphorescent algae. Star-fragments sparkled under the fluid of shadow and went still.

I put it down on the table and wrapped it in their table cloth. Anything they hadn’t already seen, I didn’t want them seeing now.

“It’s real. Decide who’s coming. I want to leave Hyperion tonight.”

The room exhaled again.

“’You taking the table cloth?” asked Nurim.

“I’m taking the table cloth.”

“Take the table cloth.”

A number of lower intensity negotiations happened. I said I’d stay away from the table provided no one else came close. They agreed, but Zenjin said he’d cover me. I agreed but wanted him to put the gun away. They hashed out who was coming with me and decided on Zenjin, Osret, and Aesthus. I ate the rest of their bread. That I wouldn’t tell them where the money was didn’t bother them. They expected that. Likewise, I expected their refusal to leave me alone for any reason until they’d been paid.

“That includes using the water house,” said Zenjin, waving his finger. “If you’ve got to drop a package, we’re going to be in the stall with you.”

I nodded. If three of them joined me in a stall, we’d better be really friendly, and we were not that friendly. But none of them were going to go alone.

I thought of them as one entity, the cousins Hemlin. That entity would stay close until paid.

They’d also eaten and snacked. We left Nurim and Apseto, and headed out into the city.

I carried the saber, and Zenjin walked behind me. Osret walked with him. Aesthus took at my left side, and I carried the saber in that hand. Osret had given me a gym-bag for my wet clothes, which was quite clever because now I had a bulky thing in each hands. The saber was too long to fit in the bag.

They weren’t stupid. They’d made a few mistakes, but they were smart people trying to think their way through hard problems with very little warning and no experience. I felt better that I was going to pay them and leave.

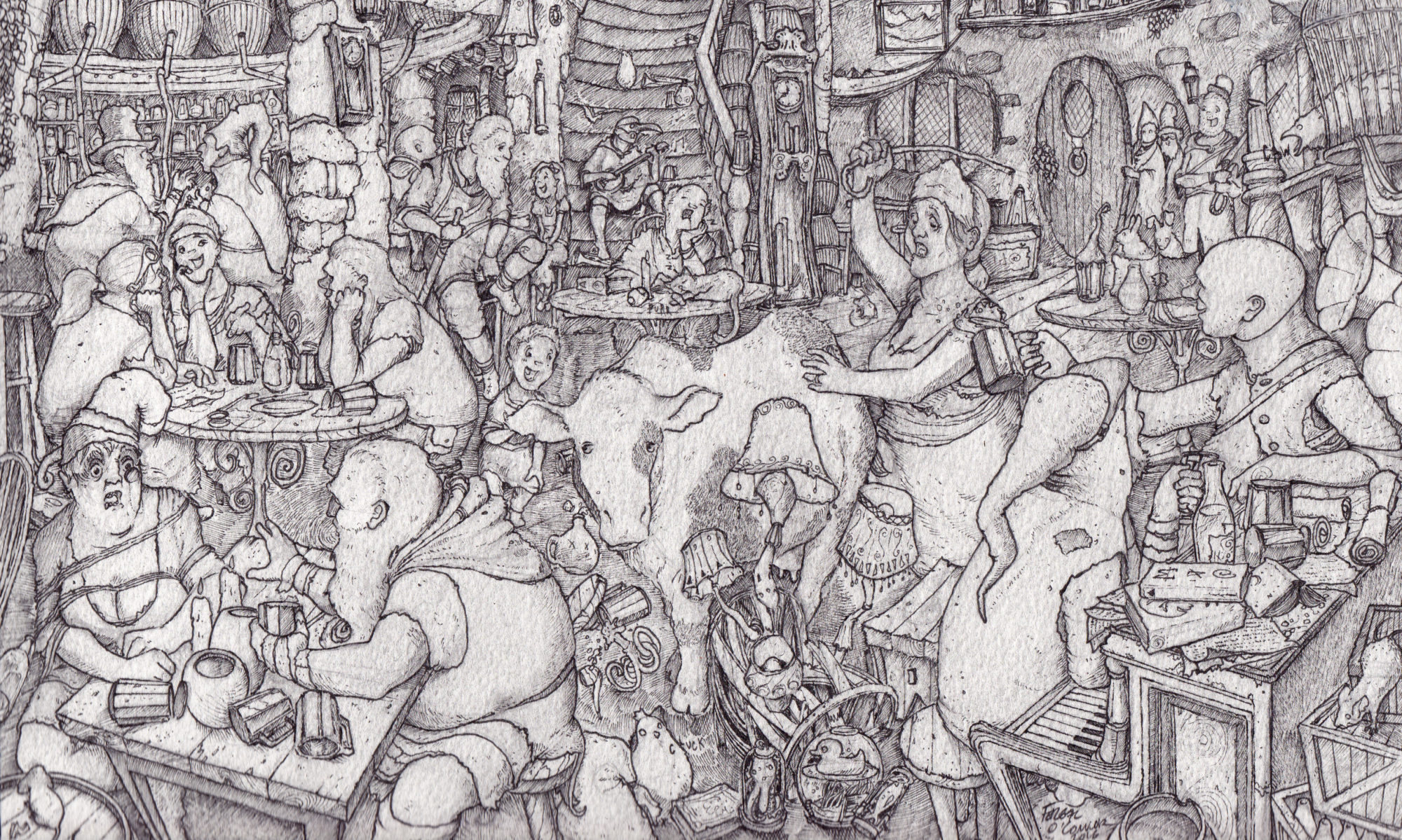

The first drop had been a little lending library in the Anentine neighborhood. The Anentines, a collection of insecure new gods that coalesced into a pantheon to stop other people from making fun of them, built immense, empty palaces with tiny backyard houses. They threw a lot of dinner parties, spent fortunes on candles for their unoccupied mansions, and lived in their tiny houses. Most were nature aligned in some way. The little lending library I went to had stood on a small pole mostly engulfed by a wild hedge, an idiotic bit of gardening fashion that I found quite useful. The hedge was no longer wild.

It wasn’t anything. Nor was the lending library. Mallens had stomped it into a hole through the crust of the earth. I saw sandstone and lime, thicker marble, black basalt, and deeper bedrock until vast drive gears loomed underground like hidden shapes.

The cousins Hemlin observed me looking at the crater. Eyes narrowed. Frowns hardened. I did a little mental trig. The library had been in the center of that crater.

“Keep walking,” I said and set off quickly.

I felt the cousins glancing between each other, watching me, looking at the buried hole. I felt like the empty houses hid dozens of watchers. I had to fight down the notion that the Hemlin cousins were going to figure out I had lied about everything and they’d know what I’d done. I kept walking.

The next drop was much simpler. I’d wrapped the package in wax paper, waterproofed it with more, and dropped it into a horse trough. They say the stables of Hyperion are always clean, but this one had some algae growing in it. Rain gutters fed it from the stable’s roof.

The trough was arm-deep, so I dropped the gym-bag, held the wrapped saber, and stuck my arm in. Without words, Aesthus kept a watch, Zenjin watched me, and Osret watched them.

The package was there, but it had gotten stuck. I had to use some muscle. The Hemlins were big guys, and any of them could have done it easier. I didn’t ask, and they didn’t offer.

I yanked it out, took the gym bag, and we ducked into the stable. The horses didn’t care.

“Somebody got a knife?” I asked.

Osret did. “Give me the package. I’ll open it.”

“Just let me use your knife. I’ll open it.”

Glances shot between them. Aesthus nodded. Osret ignored him. Zenjin finally nodded, but Osret refused him too. I really didn’t want to use the saber.

“There could be anything in there,” argued Osret.

“There’s money and my stuff. It’s not weaponry or dangerous, but it’s mine,” I said.

“I’ll just open it–”

“Don’t do that,” said Aesthus, for the first time sounded tired and short. “If it’s booby-trapped, I want it to go off on him.”

Osret froze. “Is it booby trapped?”

“Of course not.”

I didn’t even fake lie. They weren’t going to believe anything I said anyway.

Unhappily, Osret gave me a stubby pocket knife. I’d sealed the package well, so I had to scrape sealing-wax aside. Zenjin moved out at an angle, standing by a tack rack, and drew that piece of his again. He kept it down, but I was getting quite tired of the way he went for it everytime something happened.

Maybe he’d just bought it.

I put the box on the ground so everyone could see it, squatted, and opened the wooden box. It had a sliding lid, the outside of which was damp. Inside, packed in cedar shavings, rolls of silver coins lay in wax rolls. Each coin bore Mallens’s seven-pointed crown, the points capped with glittering fragments of real stars, and the edges rippled with alloyed adamant. Each coin was worth five thousand sesteres, and I’d packed five rolls of five.

Without uttering a word, I gave all five rolls to Osret.

He unrolled one, inspected the coins, and gave them to Aesthus. The two of them went through each coin. Zenjin watched, and I could see his shoulders clench. He kept leaning forward when they picked up a silver piece and held it to the faint light of the stable. But he stayed cautious, back, and tried to look everywhere at once. Osret offered him a roll of money. He declined to keep both hands on the gun.

The package also had four wax-paper rolls of ambrosia. I took one out, opened it so they could see what it was, and offered them a wafer. It had dried out. They declined. I popped one, chewed and swallowed, and hid the rolls in my clothing or in the gym-bag.

I took out four sets of passage documents and hid them in the gym-bag. The package also had a tiny idol of Limatra, the Autumn Goddess of Good Luck and Found Wealth. She was four inches tall, standing, with one hand out, two others clasped, and one loose at her side. The loose one was a hidden switch for a spring-loaded blade. I showed her as well before putting the idol in a pocket.

The package also had a dead rat. I hadn’t put it there, and it worried me immensely. I threw it to a hungry plant, which woke up long enough to eat the rodent corpse. On a hunch, I threw the plant the box too, as well as the wax paper and as much wax as I could scrape off the ground.

“That was one twenty five. Of the next package, I will give you one hundred and twenty five, and our business will be done. Do we all agree?” I asked.

“Yeah. Let’s go,” said Aesthus.

We left. Our walk was a little easier, significantly less tense. Payment breeds loyalty, and while they gave me no loyalty, I had bought a little trust. I popped a few more ambrosia wafers.

Ambrosia’s the stuff. If you want to really put on mass, you lift heavy, eat ambrosia, train, eat ambrosia, and lift heavy again, all in the same day. You can get huge, and you don’t get the aches and pains of low-lifting. I used to do strength circuits every morning, four hours of combat in the afternoon, pop ambrosia, do it again, and sleep like bliss. I hadn’t worked out hard in a couple of weeks as that assassination thing had been taking up my time, but the ambrosia did its work. I was feeling better than ever.

The next drop point was a similairly waxed package, hidden in the dirt under some flowers. They formed a small garden, not two feet wide, that ringed a large flower-shaped fountain, one that spouted like pedals. It was a little park, mostly out of the way, and not exactly hidden but not easily seen either. I had worried about this one, because the dryads who tended such gardens could easily have found it. They hadn’t.

I took the package, the four of us dipped into a parking area, and hid between two carriages. The carriage horses, mules, goats, lions, or whatever had been stabled elsewhere, and the leading harnesses stripped. The carriages were tall, four-wheeled things, capable of carrying four important passengers in comfort and perhaps half a dozen servants on varying benches, platforms, and fold-away chairs. Not only was the carriage yard concealed by a tall wall, through with there was only one gate, but no one in that direction could see us through the carriage anyway.

I held the package up so everyone could see it too was thoroughly wrapped in wax paper. I asked for the knife, and Osret refused.

“No. I’m opening that one. I don’t know what your game is, but you’re up to something. Give it to me.”

Sickness take me, I should have given it to him and left. But there was ambrosia, and I needed it. There was an idol of Arya who hid secrets, and I thought I might keep her around. So I stayed for a bunch of stuff when I could have just given them the box and ran.

He took out his knife to cut it open and stopped. “Would you back up a little bit? You’re in my space.”

I wasn’t—well, I was in his space, but the space between the carriages wasn’t that big. I backed up.

“And you,” Osret said to Zenjin, who’d pulled his Puritan again. “Watch him.”

“I am watching him!”

“Not enough! Watch him like the Sun. Point the gun at him or something. He got a little loose last time he opened one of these.”

“Oh, blisters on you,” snorted Zenjin. He glared at me.

Aesthus looked like he wanted to avoid an argument, so he took a step away too.

Osret crouched down but shifted the box to his knife hand. He put his other hand on the bottom. I looked away for a split second at Zenjin, who was almost flagging me with the Puritan, and noticed some movement in Osret’s hands. I looked back.

With gun in his other hand, the one concealed underneath the package, Osret shot Zenjin twice in the chest. Something banged like sledgehammers on steel and blew Zenjin’s ribcage out his back.

Aesthus screamed, and Osret shot him too.

I bolted from the carriages and ran for the road.

Osret ran around the other side, tracked me across the parking-lot with his holdout gun, and sent rounds after me. Two missed.

The third did not.

For a holdout gun, that thing kicked like a horse.

He got me in the shoulder, I dropped and skidded on my face, and Osret walked me down. The saber fell a dozen yards away.

Before shooting, he said, “Sorry, Remus. I don’t know who you are and don’t care. If it makes you feel better, I don’t think you’re a bad guy. But I can’t have people knowing what happened here.”

Glory, I wish I had that forged sword. It was right there. But Osret was closer, and he drew a bead.

I flicked the hidden switch on the idol of Limatra, the spring-loaded blade shot out, and stabbed him through the center of the forehead. Luck was with me. He blasted wide, emptying his cylinder into the wall by the saber.

But I wasn’t there. I’d gone the other way, out the gate, and fled the parking lot. Everything was wasted, and I still didn’t have the sword.